The Great DBE Shake-Up (2025): How USDOT Froze Billions in Federal Contracts Overnight

In October 2025, the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) detonated a regulatory earthquake. Its Interim Final Rule (IFR) erased decades-old race- and sex-based presumptions from the Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE) program, forcing every certified firm to prove individual disadvantage.

The fallout? Thousands of projects nationwide paused or amended, more than $20 billion in megaproject funding under review, and roughly 41,000 firms headed for recertification.

The Day the Rules Changed

On October 3, 2025, the IFR hit the Federal Register like a thunderclap. Overnight, DBE certification shifted from group presumption to personal proof. Every highway, transit, and airport project using federal funds suddenly had to stop counting DBE participation and halt new goal-setting until each state’s Unified Certification Program (UCP) reevaluates every firm.

Within a week, the tremors reached California. Metrolink issued a formal notice: “All DBE goals are suspended. Active solicitations reset to 0%.” Other agencies followed suit.

ENR confirmed that USDOT estimates 41,000 firms must undergo re-review and that recipients may not set DBE goals during the process. That’s not a tweak, it’s a total system reboot.

Billions in Projects Suddenly on Ice

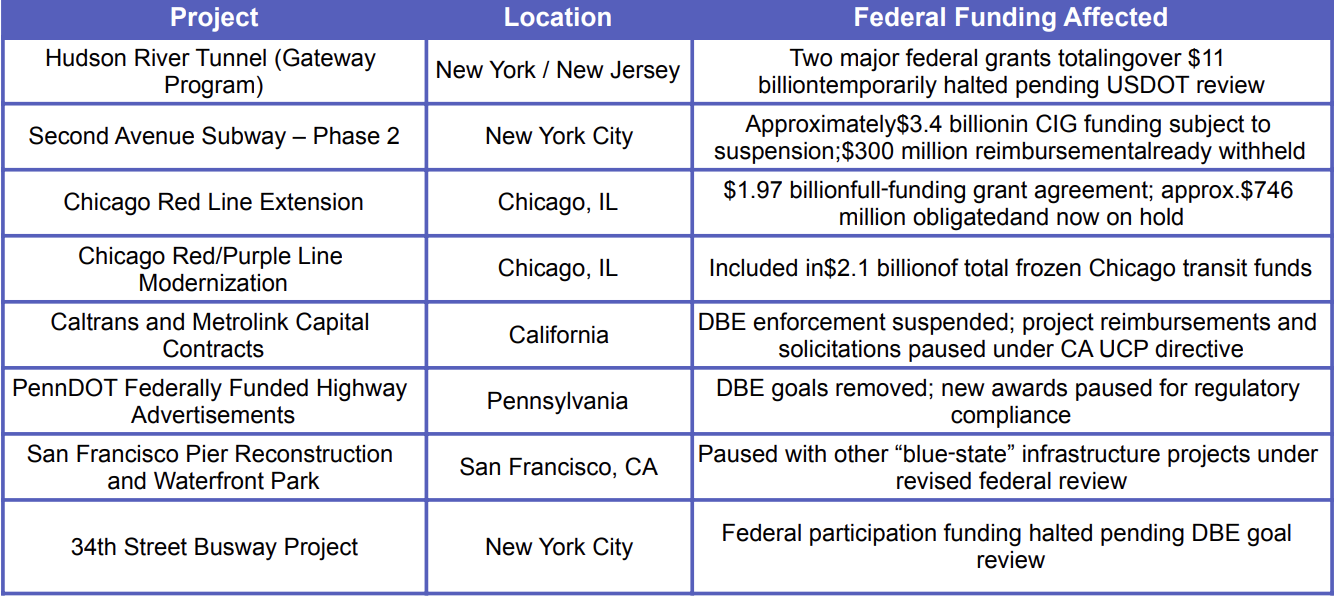

USDOT’s October 1 press statement announced reviews into “unconstitutional contracting practices” in New York. Two megaprojects were immediately caught in the dragnet:

Second Avenue Subway (Phase 2), $300 million reimbursement halted

Hudson Tunnel (Gateway Program), nearly $18 billion in federal funding under review

Meanwhile, in Chicago, federal officials paused roughly $2.1 billion tied to the CTA Red Line Extension and Red/Purple Modernization.

That’s more than $20 billion in marquee infrastructure work frozen pending review.

How Big Is the Impact?

Under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (IIJA), the federal government has committed $215 billion across 100,000+ highway and bridge projects since 2021. Add thousands of transit and airport projects under Parts 23 and 26, and the scope is enormous.

Inference (based on official USDOT data): while not every one of those contracts carried DBE goals, nearly all are procedurally affected, contract clauses, compliance reports, or payment tracking now require modification. That’s thousands of live procurements suddenly running with “zero-goal” language until states finish recertification.

The States Feeling It Most

Texas – $5.485B

California – $5.160B

Florida – $2.664B

New York – $2.360B

Pennsylvania – $2.307B

These high-volume states administer the largest portfolios of DBE-goal contracts, so they face the steepest administrative load. California and New York are ground zero, Caltrans, High-Speed Rail, and Metrolink all issued alignment notices within days, while PennDOT formally suspended its goals statewide.

Why the DBE Program Existed

The DBE program was born in 1983 to ensure socially and economically disadvantaged businesses, primarily minority- and women-owned, could compete fairly for federally assisted transportation contracts. Congress mandated a 10% national goal, later codified in 49 CFR Parts 23 and 26.

In 1987, women were added as a presumptively disadvantaged group. For forty years, the system relied on those presumptions to speed certification and correct historic inequities.

But as court rulings and politics shifted, especially cases like Mid-America Milling Co., the legal ground beneath the DBE framework began to crack. The 2025 IFR is the response: a race-neutral rewrite aimed at surviving constitutional scrutiny.

A Clash of Principles

USDOT Secretary Margaret Duffy was blunt: “Subsidizing contracts based on discriminatory principles is unconstitutional and a waste of taxpayer resources.”

Advocates counter that the change raises barriers for minority- and women-owned firms, many already operating on thin margins.

Here’s where the rubber meets the road. If each UCP must re-vet thousands of firms with limited staff, it could take 6–12 months before normal DBE goal-setting resumes, an eternity in construction time.

What Happens Next

Re-certification marathon: All 41,000 DBEs must submit personal narratives, financials, and control documentation.

Contract modification wave: Agencies will issue addenda resetting goals to 0%.

Legal storm brewing: Civil-rights coalitions are drafting APA challenges.

Administrative gridlock: Expect mixed guidance, delayed payments, and nervous auditors.

What Contractors & Leaders Should Do

Stay close to your state UCP.

Monitor recertification instructions.

Prime contractors: Document outreach even under “zero-goal” solicitations.

DBE firms: Prepare narratives and financials now.

Agency officials: Plan for contract mods and communicate clearly.

The End of the Presumption Era

For forty years, the DBE program symbolized the federal commitment to inclusion in public contracting. The 2025 rule doesn’t kill that ideal, it redefines it under a stricter constitutional lens.

Whether this shift yields a fairer system or merely a fairer-looking one will depend on execution: how fast UCPs move, how well agencies communicate, and whether disadvantaged entrepreneurs can navigate the new maze without getting lost.